Brando Essay

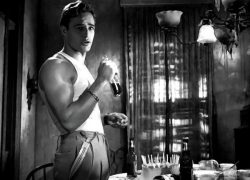

Marlon Brando burst onto the international film scene like an enraged gorilla as Stanley Kowalski in Tennessee Willliams’ A Streetcar Named Desire. He was physical, unpredictable, moody, violent, uncouth, completely spontaneous and disturbingly sexy.

Most film audiences had never seen an actor like this before. Two earlier Method actors, John Garfield and Montgomery Clift, had had something Brando’s impulsive realistic technique, but not until Brando did an actor make an audience so uncomfortable.

Not long after Streetcar, in The Wild One, Brando terrorized a small town as the leader of a motorcycle gang. But he wasn’t just the typical nasty tough guy that audiences had seen so many times before. His sensitivity and introspection, his self-doubt, made him interesting and sympathetic. By exploring, Method-style, the inner life and history of this character that most actors would play as a cliche, Brando brought something new to the cinema and to the craft of acting.

James Dean

When James Dean appeared in East of Eden and Rebel Without a Cause a couple of years later, audiences saw a somewhat gentler, though still unpredictable rebel. In both actors they were seeing a complex emotional life that few actors, especially male actors, had achieved previously on the screen. Other actors of this sort began to appear: Geraldine Page, Kim Stanley, Julie Harris, John Cassavetes (who went on to become America’s greatest director of independent films with his little company of Actors’ Studio trained actors), Paul Newman, Anthony Quinn and many others. And though they all shared the the spontaneous real-life quality that Brando and Dean were becoming famous for, they also embodied many sorts of characters, not always playing the sexy rebel. For this reason they were not always identified so closely with Method acting.

It was an accident of the cultural timing of Brando’s and Dean’s early films that caused Methos acting to be identified with working-class misfits. In the late 1940’s and 50’s many countries that had been devastated by World War II saw an enormous shift in their popular culture, especially the cinema. Italian Neo-Realism led the movement toward featuring working-class characters as major protagonists, with Rosselini’s Open City and De Sica’s Bicycle Thieves. And in fact, Anna Magnani’s film presence seemed distinctively Method, though she had not trained formally in the technique. Britain’s Social Realism movement motivated many rising stars (Alan Bates, Laurence Harvey, Charlotte Rampling, Simone Signoret) toward a more organic technique. In France, Belmondo, Signoret and Trintignant were finding similar qualities in proletarian characters in the Nouvelle Vague. The new heros and heroines were working-class, physical, inarticulate, unrefined and full of soul. And often backed up by the latest be-bop jazz scores, reflecting similar movements in music.

The acting technique that came to be known as the Method had its roots in Russia in the 180’s at the Moscow Art Theatre. Konstantin Stanislavski created the beginnings of a system that would use the actor’s personal experiences in the work. He did this by focusing on sensory and emotional memories. If the actors actually feels a certain way physically, emotionally, mentally and spiritually, based partly on their own experience and partly on imagination, they will tend to more fully experience the world of the play and their role, instead of acting clichés and pre-determined poses.

Stanislavski’s technique was developed further in New York at the Group Theatre, out of which came the great Method teachers, Lee Strasberg, Stella Adler and Sanford Meisner. Strasberg emphasized sense memory and the actor’s personal experience. Adler explored the actor’s imagination and insisted on great size and soul in the characterization, in keeping with her Yiddish Theatre background. Meisner was more concerned with the in-the-moment interactions between characters. Though all these approaches overlap quite a bit, there was great rivalry. Adler and Strasberg hated each other with deadly passion, and their disciples sometimes tended to follow suit. Brando, Stella Adler’s protégé, thought that Strasberg was untalented and that his technique suppressed the actor’s imagination. It must be noted however, that Brando loved working with the Strasberg-trained Al Pacino, and thought that Pacino’s work was superb!

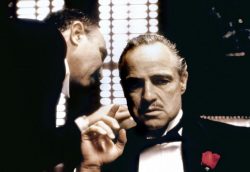

Marlon Brando in The Godfather

It’s true that one can see subtle differences fo technical emphasis in the followers of these three teachers. Brando was Stella Adler’s creature, hugely powerful with a great size to his characterizations that one might more commonly associate with the great classical actors of Shakespeare, and all the more impressive to see in in working-class modern characters who behaved realistically and couldn’t speak through a sentence in a straight line. In Al Pacino, Strasberg-trained, we see the soul revealed and the passions ignited. Audience love him because he’s the most vulnerable and human of actors. Robert DeNiro, somewhat colder and more technical, though perhaps the “purest” of actors, studied under Sanford Meisner, the master of the “here and now.” Yet in spite of their differences, most observers would tend to categorize these actors together, mainly because of their mutual ability to bring a character to organic, breathing reality.

The influence of certain directors in the realization of the work of certain Method actors cannot be ignored. Elia Kazan was hugely influential in Brando’s work, constantly challenging him to go deeper. Brando stated that Kazan would practically act the scene off-camera while he was filming Brando, his whole body moving and engaged, like an orchestra conductor trying to pull the music out of his players. Martin Scorcese can also be considered a “Method” director, particularly in his work with DeNiro, Joe Pesci and Harvey Keitel. Francis Ford Coppola directed Brando, Pacino and DeNiro (not to mention two generations of notable Method actors in supporting roles, including Strasberg himself) in the Godfather films. In large part because of Coppola’s work with these actors, The Godfather films have come to be considered one of the masterpieces of 20th century cinema. Brando’s death scene is a miracle of Method acting and direction. With almost no dialogue, Brando improvises having a heart attack while playing with his little grandson in his garden. The elements of the scene are highly symbolic (the little boy sprinkling the dead godfather with a watering can as though nurturing the generational cycle of life and death in the garden of this Mafia family), but the scene is played with the most startling realism that makes the symbols act on us unconsciously. True art never explains. Brando puts an orange peel in his mouth, then grunts and hulks like a gorilla to amuse the child, even scaring him a little, and reminding us of nothing so much as a comic Stanley Kowalski!

Marlon Brando in Streetcar Name Desire

To this day Brando’s work upsets some people, who think acting shouldn’t touch us so directly, at least not in such uncomfortable ways. I once attended a dinner in which I was seated next to a very prominent art gallery owner who was well-known for making stars of the most avant-garde and even bizarre conceptual artists on the planet. I would have thought that she would appreciate Brando’s revolutionary influence on acting and the cinema. But no. When she found out who I was, she launched into a tirade about how Brando had ruined modern acting, that he was an uncivilized animal with no sense of finer aesthetics, and that she felt threatened by the feelings he stirred within her when she saw him on the screen. She preferred more cultured actors like Laurence Olivier, actors who moved into the modern age with more grace and beauty. It struck me that this avant-garde gallerist was just a traditional upper-class elitist, horrified that the peasants had dared to invade her sacred temple of art! It also occurred to me that maybe the visual arts might just need a Bando of their own….

Written by Robert Castle, March 1, 2009. For “Marlon Brando, o ator no Cinema” the official catalogue of “Mostra Brando” CAIXA Cultura Rio. All rights reserved